Why you need to adopt a growth mindset

- Jake Gutwein

- Jan 6, 2018

- 8 min read

In recent years, a line of research has emerged surrounding the idea of a growth mindset. While the field is still in its infancy, the implications of the findings thus far are profound and can be the cause of drastic improvements in performance. In this article, I discuss what growth mindset is, why we believe our abilities are fixed, the results of applying a growth mindset, and, finally, how you can adopt a growth mindset.

What is a growth mindset?

An individual with a growth mindset is one that believes that their ability, skill, or intelligence is malleable and capable of being developed, whereas those with a fixed mindset believe that these facets are not subject to change. This means that if an question arises where the answer is unknown, the individual with a growth mindset is able to perceive this challenge as an opportunity to learn. As a result, practice is seen as the criterion for success and effort in a task is likely to be easier to undertake compared to a similar individual with a fixed mindset.

The video below from college professor John Spencer does a great job at concisely and visually explaining the difference between a fixed and growth mindset. His channel includes a variety of videos on related learning topics, so if that’s what helps you get out of bed in the morning feel free to check them out.

An important note is that thinking about having either a growth or a fixed mindset can lead to believing that it is only possible to have one or the other, when in reality it is a spectrum. Instead of believing in a false dichotomy, it is more equitable to recognize that evolving from a fixed to a growth mindset involves navigating this spectrum. One way this is manifested is through how many tasks or how often characteristics of each mindset appear, with an individual believing that they can growth their mathematics but not science skills displaying traits of both. Embracing a growth mindset is itself a process of growth along this spectrum.

The neuroscience behind the different mindsets is fascinating, though if thinking about neurotransmitters doesn’t get your blood pumping then “fascinating” probably isn’t the right word. In a study published in the journal Psychological Science in 2011, the researchers looked at “event-related potentials (ERPs) to probe the neural mechanisms underlying [the] different reactions to errors” displayed by individuals of each mindset. The results showed that one reason those with a growth mindset learn from mistakes is because they are more cognizant of those mistakes (science-ey version below).

“Specifically, a growth mind-set was associated with enhanced Pe amplitude — a brain signal reflecting conscious attention allocation to mistakes — and improved subsequent performance. That the Pe mediated the relationship between mind-set and posterior performance further underscores its significance in linking mind-set to rebounding from mistakes.”The image below, taken from the study, shows the difference between ERP on incorrect and correct trials for each group. In short, the difference in activity was far greater for those with a growth mindset versus those with a fixed mindset, which accounts for the deviation in error recognition and correction.

Why do we believe our abilities are fixed?

My argument for why abilities are often perceived as fixed is that the brain wants to craft a compelling cause-effect narrative for why things occur. Therefore, when an individual attempts to define why they failed at a task, it is easiest to think that they were simply not fit for the task. In his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman writes that “we are evidently ready from birth to have impressions of causality, which do not depend on reasoning about patterns of causation.” One of the flaws that arises from this is the confirmation bias, meaning that those who enter an activity believing that they have fixed abilities and putting in minimal effort will, once they fail at that task, be able to claim that their failure was caused by the fact that they have a certain fixed ability.

Moreover, if they are compare their performance on a task to another individual that performed better and the only knowledge that they have about the other individual is that they took the test as well, they are likely to think that the other individual was simply naturally better at performing that task. This connects to another idea in Kahneman’s work, where he notes that individuals are prone to “jumping to conclusions on the basis of limited evidence,” which “facilitates the achievement of coherence and of he cognitive ease that causes us to accept a statement as true.” The low score individual attributes the performance of the high-score individual to their innate skills as that appears to be the only causal explanation for the difference in scores. What is missing from this, however, is what appeared outside of the task’s setting, which includes practice, growth, and studying.

Another reason fixed mindsets are so prevalent is the type of praise that is received. Claudia Mueller and Carol Dweck came to this conclusion after performing six different studies on fifth grade students. In a write-up for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Dweck writes that “praising students for their ability taught them a fixed mindset and created vulnerability, but praising them for their effort or the strategy they used taught them the growth mindset and fostered resilience.” The fact that individuals, not just students, are evaluated constantly on their performance makes them susceptible to failure, and the easiest excuse for this failure is to simply claim that they would not have succeeded regardless of how much effort they gave because they lacked the innate ability.

How does a growth mindset alter our abilities?

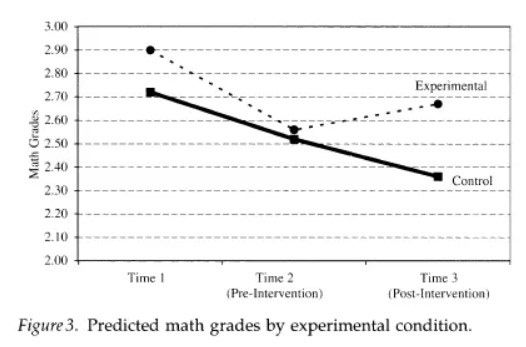

One study, performed by Lisa Blackwell, Kali Trzesniewski, and Carol Dweck, published in the journal Child Development, longitudinally examines students of each mindset and their growth. 99 students were separated into two different groups, with the two groups being approximately equivalent in previous academic achievement measures and “baseline motivational constructs.” The researchers utilized eight 25-minute sessions throughout the time of the study which were constructed as workshops to learn about the brain and study skills, though the experimental group “were taught that intelligence is malleable and can be developed.” Following this intervention, as shown in the figure below, predicted math grades were approximately 12.5% higher for the experimental group — showing the value of the growth mindset.

Another study, from the University of Washington and Stanford University, examined the impact of having a growth mindset in the context of educational games. In their experiment, the researchers used two versions of an educational video game — a control which “provides a neutral view of intelligence,” and an experimental which “teaches and rewards growth mindset behavior by leveraging the game’s narrative and incentive structure.” The results were, again, stunning, with the children who played the experimental version of the game spending more time on problems that they were challenged with than the control version children. This allowed the researchers to conclude that “the growth mindset feedback has the potential to increase persistence and performance in educational games.”

If you wanted to know how growth mindsets impact companies, Carol Dweck, the founder of the field of study, has an answer. Essentially, the companies who fell more on the growth side of the mindset spectrum were far more likely to capitalize on innovation-the same innovation that is now being recognized as the key to long-term growth. She notes the following:

“When entire companies embrace a growth mindset, their employees report feeling far more empowered and committed; they also receive far greater organizational support for collaboration and innovation. In contrast, people at primarily fixed-mindset companies report more of only one thing: cheating and deception among employees, presumably to gain an advantage in the talent race.”How do we adopt a growth mindset?

Number 1: Accept that your abilities can be changed. Neuroscience defends the conclusion that change is possible, with recent advancement in studies of neuroplasticity solidifying this point. In short, practice is a tool that grows the total amount of connections in neural networks and allows performance to improve over time. For example, the first time you attempt calculus problems you may have to reference the textbook or notes to determine how to solve each type of problem. After a few examples have been examined, however, you will be able to more easily recognize the way to solve each problem type as the access to and strength of your neural networks has grown.

The video below from Sentis, a channel discusses “psychological and innovative solutions to everyday business challenges,” does a great job at simply explaining how this happens.

Number 2: Don’t give up after an initial failure. One of the key differences between those with a growth and fixed mindset is the ability to respond to failure. This was shown in the study examining the ERP for the two types of mindsets earlier, and Hans Schroder, the lead researcher, followed-up the findings by saying that “the main implication here is that we should pay close attention to our mistakes and use them as opportunities to learn.” When faced with a challenge or adversity, it is important to recognize that many challenges aren’t supposed to be accomplished the first time they are undertaken — otherwise they wouldn’t be considered challenges. Instead, you ought to understand that the key differentiator between those who eventually succeed and those who repeatedly fail is the desire to grow after the initial failure.

“I think it’s very important to have a feedback loop, where you’re constantly thinking about what you’ve done and how you could be doing it better.” — Elon MuskNumber 3: Think about the task. Interestingly, thinking about a task has many of the same neurological impacts as actually performing that same task. An article from Authenticity Associates shows that “mental activity strengthens the neural pathways in your brain associated with what you focus on with your thoughts and feelings[…]every thought you think and feeling you feel, strengthens the circuitry in your brain known as neural pathways.” Even if you are not physically performing the task in question, you can improve your performance by thinking about that task.

This concept was discussed in a 1989 study by Lori Eckert, where the impact of mental imagery on free throw performance was examined. Subjects in the study were assigned to one of three groups, either receiving mental practice, physical practice, or both. The group that received both mental practice and physical practice showed the most improvement over time, greater than the physical practice group and far above the mental practice group. Again, this shows the importance of thinking about a task in order to gain the extra edge in growing and achieving eventual success.

Number 4: Change the way you evaluate performance. During the process of reflecting on your performance, it is critical to consider the reasons why you were limited to a certain result. By ruminating on these aspects, you will be more aware of the issues that caused the sub-optimal score and be far better equipped to focus on these aspects during the growth process.

When inspiring students in schools or employees in companies, Dweck encourages the rewarding of effort but, notably, limits the type of effort that should be encouraged. Dweck writes in her Harvard Business Review article that “it’s critical to reward not just effort but learning and progress, and to emphasize the processes that yield these things, such as seeking help from others, trying new strategies, and capitalizing on setbacks to move forward effectively.”

In addition, the growth mindset should be considered during evaluation of employees. Employees, understandably, may feel pressured by their annual review as they see it as a source of evaluation of their performance over the past year. While performance can sometimes be simplified into something like a sales number, this does not tell the whole story as exogenous factors can often impact numbers and these numbers fail to consider the steps the employee has taken to grow. This prompts the inclusion of questions related to the effort taken to improve performance over the next year, particularly emphasizing new methods or techniques that could be undertaken.

Still want to learn more?

If you aren’t yet satiated learning about the growth mindset or want to see Carol Dweck speak on her research, I’ve put a couple videos below. If you want to take a look at more of the benefits of living your life with a growth mindset perspective, check out this post.

Comments